History

Explorers

On February 2, 1829 Charles Sturt was the first european (explorer) to discover the darling river.

Sturt’s 1828 expedition was sent out by Governor Ralph Darling to solve the riddle of the Macquarie River and the other western rivers. The Macquarie river had been followed before by the late John Oxley in the years 1817 and 1818, but the large marsh or marshes had stopt hes progress. Oxley favoured the idea that the Macquarie marshes were on the edge of the inland sea

It was assumed, correctly, that because of the long drought which began in 1826 and continued with increasing severity until after the expedition had returned, that the marshes, by the water-logged condition of which Oxley had been stopped, would be very much drier and that the difficulties Oxley had met “would be found to be greatly diminished, if not altogether removed.

His discovery of the ‘Darling’ river on

(). On discovered the darling on

eBy His Excellency Lieut.-General Ralph Darling.

To Charles Sturt, Esq., Capt. in the 39th Regiment of Foot.

Whereas it has been judged expedient to fit out an expedition for the purpose of exploring the interior of New Holland, and the present dry season affords an excellent prospect of ascertaining the nature and extent of the large marsh or marshes which stopt the progress of the late John Oxley, Esq., Surveyor-General, in following the courses of the Rivers Lachlan and Macquarie in the years 1817 and 1818:

xpedition for the purpose of exploring the interior of New Holland, and the present dry season affords an excellent prospect of ascertaining the nature and extent of the large marsh or marshes which stopt the progress of the late John Oxley, Esq., Surveyor-General, in following the courses of the Rivers Lachlan and Macquarie in the years 1817 and 1818:

A severe drought in New South Wales in 1826-7-8 led to the discovery of the River Darling. In 1818, an earlier explorer. Oxley, had been prevented by swamps from continuing his survey of the Macquarie River. Governor Darling, thinking that the prolonged drought might have dried up the swamps, appointed Captain Charles Sturt to complete Oxley’s work.

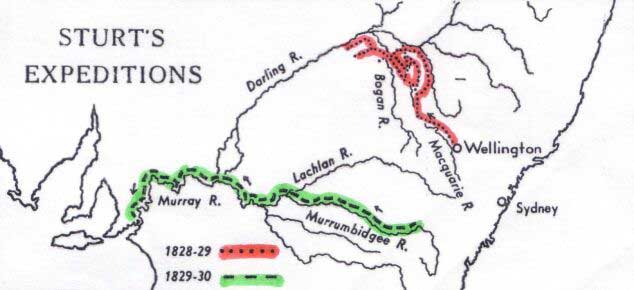

Sturt left Wellington, N.S.W., , and, proceeding past the marshes which Oxley had considered to be the termination of the Macquarie, followed the course of the Bogan River, dry except for occasional pools, until in February, 1829, he reached a river which he named the Darling.

On a later expedition, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River down to its junction with “a broad and noble river” which he named the Murray. Actually it was the same river that the explorers Hume and Hovell had crossed in 1824, and called the Hume. Sturt explored the Murray down to its mouth

On this exedition Sturt also

In 1828 the explorer and Hamilton Hume were sent by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Ralph Darling, to investigate the course of the Macquarie River. He discovered the Bogan River and then, early in 1829, the upper Darling, which he named after the Governor.

In 1835, Major Thomas Mitchell travelled a 483 km portion of the Darling River. Although his party never reached the junction with the Murray River he correctly assumed the rivers joined.

In 1856, the Blandowski Expedition set off for the junction of the Darling and Murray Rivers to discover and collect fish species for the National Museum. The expedition was a success with 17,400 specimens arriving in Adelaide the next year.

(28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869)

Captain Charles Napier Sturt

In 1828 the explorer Charles Sturt and Hamilton Hume were sent by the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Ralph Darling, to investigate the course of the Macquarie River. He discovered the Bogan River and then, early in 1829, the upper Darling, which he named after the Governor.

On 4 November 1828 Sturt received approval to proceed with his proposal to trace the course of the Macquarie River. Prudently he selected as his assistant the native-born Hamilton Hume, who had already shared leadership of a major expedition to the south coast.

With three soldiers and eight convicts Sturt left Sydney on 10 November. Hume joined them at Bathurst and, after collecting equipment from the government station at Wellington Valley, they moved on 7 December to what became virtually the base camp at Mount Harris.

On 22 December the expedition started down the Macquarie through country blasted by drought and searing heat. Having unsuccessfully tried to use a light boat, on 31 December Sturt and Hume began independent reconnaissances in which Hume established the limits of the Macquarie marshes and Sturt examined the country across the Bogan River. They then proceeded north along the Bogan and on 2 February came suddenly on ‘a noble river’ flowing to the west; Sturt named it the Darling.

Unhappily its waters were undrinkable at that point because of salt springs. They followed the Darling downstream until 9 February, then returned to Mount Harris and from there traced the Castlereagh northward until it too joined the Darling. They then returned to Wellington Valley down the eastern side of the Macquarie marshes, having sketched in the main outlines of the northern river system and discovered the previously unknown Darling River.

The expedition, however, had discovered no extensive good country. Although Sturt was ill on his return to Sydney he was scrupulous in recommending the convicts in his party for such indulgences as the colonial government could grant. Darling granted some remissions of sentence and in his dispatches commended Sturt’s patience and zeal.

(28 April 1795 – 16 June 1869)

Captain Charles Napier Sturt

The accuracy of his judgment is notable. A journey to-day anywhere in the area between Warren, Brewarrina, Bourke and Nyngan bears out, in every mile, every word of that verdict of the first white man to see it.

Also, when they compared their respective routes, Sturt and Hume agreed that their tracks must have been very near each other at the Bogan River. This left open the remote possibility that the lower reaches of the Macquarie had been between the two routes and had been missed by both of them. This was too important a point to be’ undecided, and it was also necessary to gain more information as to the nature of the “distant interior”: their provisions were getting low and there was no time to lose. They decided to go north along the eastern side of the marshes and turn west as soon as they could force a way through the reeds.

The story of this journey in its geographical aspects can quickly be told. Hume, with the party, moved slowly north and camped on Bulgeraga Creek, while Sturt made a hurried trip to Mt. Harris hoping to find that supplies had arrived there.

On the second day Hume took the party along Bulgeraga Creek till that creek lost itself in the marshes and then continued northwards for another fifteen miles. This would bring them to a point almost due west of Quilbone (perhaps about Portion 3 Parish of Molle).

Here Sturt joined them and immediately took the whole party westwards, forcing their way through the reeds and emerging on to a vast plain.

Leaving this plain (13th January) they went westward to Marra Creek (Sturt’s Duck Creek) reaching it at about Narrawin, followed it northerly for seven miles, then turned westward, reaching the Bogan due east of New Year’s Range: just before reaching the Bogan they crossed, on the same day, both Sturt’s and Hume’s tracks of the previous journeys, as they had anticipated. The party camped (17th January) on a water-hole under New Year’s Range. From this camp Sturt and Hume made a short journey southerly over the claypan to the neighbourhood of Stony Hills, north-east of Coolabah, returning to the camp the following day to find one of the men, Norman,* missing.

(*See p. 24.)

From this camp the party moved back to the Bogan to a point where a bar of red granite crosses the river. The actual point of contact would be somewhere between Gongolgon and Pink Hills. They followed down the Bogan to a point almost due east of Oxley’s Tableland to which they moved on 23rd January. Here the main party camped while Sturt and Hume made a journey to D’Urban’s Group. The nature of this group of hills and of Oxley’s Table Land evoked in Sturt’s mind the concept of these ranges being like islands in the midst of the ocean, “only wanting the sea to lave the base.” The inland sea was never far from his mind.

At this point Sturt abandoned all idea of journeys further westward–the water problem had been acute for days. On his return to the camp Sturt moved the whole party (31st January) back to the Bogan to the point where that river turned westward along the course now known as the “dry Bogan”: this course they followed westward, and, leaving this river bed in a general northerly direction, came suddenly, on 2nd February, on the great watercourse of the Darling–a “noble river” the water of which was unhappily salt.

“I found it extremely salt, being apparently a mixture of sea and fresh water. Whence this arose, whether from local causes, or from a communication with some inland sea, I knew not, but the discovery was certainly a blow for which I was not prepared.”

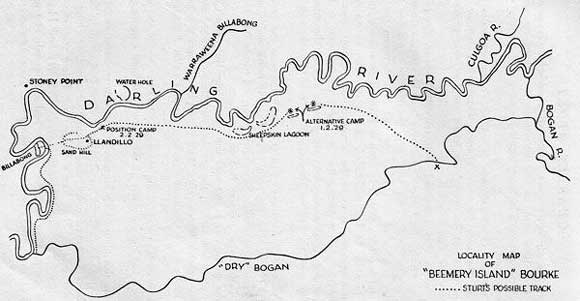

The point at which Sturt discovered the Darling can be determined with reasonable approximation. It is indicated by three features, a reef of rocks near a considerable loop in the river, a distance of approximately four or five miles from the Darling–dry Bogan junction, and Sturt’s comment:

“If I might hazard an opinion from appearance, to whatever part of the interior it leads its source must be far to the northeast or north.”

The rock bar which appears to answer Sturt’s description was probably at a place described in some of the old records as St. Vincent’s Point which was very close to what is now known as Stony Point–the critical point at which the Darling turns sharply from a set westerly course to a permanently south-westerly one.

After crossing the “dry” Bogan the route followed by Sturt is shown in the sketch prepared by Mr. W. K. Glover, of Llandillo Station. This route accords so closely with the description given by Sturt that it may be accepted, in view of Mr. Glover’s comprehensive knowledge of the locality, as being reasonably accurate.

Sturt first pitched camp on the Darling at the point where the Llandillo pumping plant is now located about three miles upstream from Stoney Point (the point of first contact is about 8 or 9 miles upstream from Stoney Point): and the point at which Hume found fresh water is, as shown, approximately two miles south of Stoney Point. In “traversing a deep bight” the party must have passed very close to Llandillo homestead, which is located on the sandhill crossed by Hume.

They followed the Darling downstream–passing the site of Bourke about 4th February–until 9th February, when they turned back, having reached a point a little south of Redbank.* Before they left this end point of their journey Hume carved his initials on a tree: these were seen by Mitchell in 1835 and the place was pointed by Mitchell as 53 degrees E. of S. from D’Urban’s Group. At this turning point Sturt named the river the “Darling”: “to pay by this trifling mark of respect some part of the gratitude I owe to the present Governor of the Colony.”

(* See Appendix, Note. 2.)

They had found the water too salt to drink throughout the whole course of their journey down the Darling: “I certainly thought we were rapidly approaching some inland sea”: but before they left the Darling he knew that the saltness was due to springs of salt water in the bed of the river

A single glimpse of it was sufficient to tell us it was the Darling. At a distance of more than ninety miles nearer its source, this singular river still preserved its character, so strikingly, that it was impossible not to have recognised it in a moment. The same steep banks and lofty timber, the same deep reaches, alive with fish, were here visible as when we left it. A hope naturally arose to our minds, that if it was unchanged in other respects, it might have lost the saltness that rendered its waters unfit for use; but in this we were disappointed—even its waters continued the same.

I found and left the Darling in a complete state of exhaustion. As a river it had ceased to flow; the only supply it received was from brine springs, which, without imparting a current, rendered its waters saline and useless, and lastly, the fish in it were different from those inhabiting the other known rivers of the interior.

It is true, I did not procure a perfect specimen of one, but we satisfactorily ascertained that they were different, inasmuch as they had large and strong scales, whereas the fish in the western waters have smooth skins.

Tributaries

Where does the water come from?

Darling Riverine Plains

Biodiversity and Vegetation

Landforms are typically channels, floodplains, and swamps of past and present river systems. The vegetation in these subregions is generally River Red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) on channels and lake margins while lignum (Muehlenbeckia cunninghamii) occurs in swamps and open water. Mitchell grass (Astrebla spp.) with few trees occurs on clay plains. Coolabah woodland (E. intertexta), River Cooba (Acacia bivenosa), Western Bloodwood (Corymbia terminalis) and Mulga Leaf Ironbark (Eucalyptus sp.) may also occur in the headwater subregions while white cypress pine (Callitris columellaris) may be supported on some sandy soils.

Between Bourke and Wilcannia in the Louth Plains and Wilcannia Plains subregion the geology is dominated by the alluvial plains of the mid-Darling valley where shallow Quaternary alluvial sediments overlay bedrock. Landforms consist of channel and floodplain features with anabranch streams feeding valley margin lakes. There are also limited areas of dunes and sandplain. Soils are typically grey clays from channels to backplains with limited areas of higher red soils and patchy sands probably representing alluvial terraces. Coolabah, river red gum, river cooba and some black box (Eucalyptus la.giflorens) occur along the channels. Canegrass and lignum occur in depressions, with saltbush (Atriplex spp.), bluebush (Maireana spp.) and grasses on backplains. Poplar box (E. populnea), rosewood (Heterodendrum oleifolium) and some black box (Acacia melanoxylon) occur on red soils and valley margins.

Within the Lower Darling River the Menindee, Great Darling Anabranch and Pooncarie – Darling subregions are again dominated by Quaternary alluvial deposits. Complexes of river and lake sediments with associated aeolian landforms such as Channel and floodplain features, well developed anabranch streams and overflow lakes with lunettes and extensive sandplains and low dunes dominate these three subregions. Soils are typically grey clay and white sand in channels, lake beds and beaches. Brown clays occur on swamps, merging to red sands and some texture contrast soils on sandplains. Lunettes of white or pale yellow sand alternate with layers of pale brown pelleted clay. River red gum, river cooba and black box occur along the channels and lake margins. Canegrass and lignum are present in swamps and depressions. Saltbush, bluebush, turpentine (Acacia lysiphloia), prickly wattle (Acacia tetragonophylla), and grasses with belah (Casuarina pauper and C. cristata), and rosewood (Alectryon oleifolius), occur on red soils while bluebush and sandhill canegrass occur on lunettes.